How do we reverse

the brain drain?

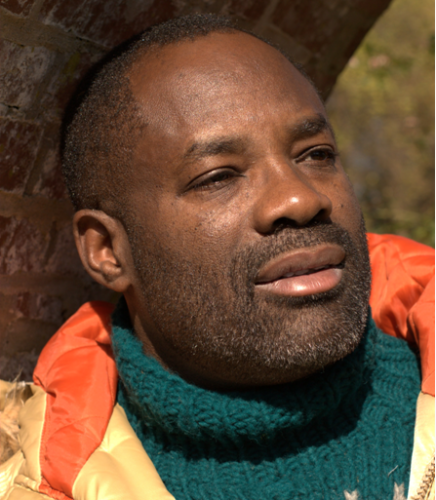

Keynote speech by Philip Emeagwali at the Pan African Conference on Brain Drain, Elsah, Illinois on October 24, 2003.

Thank you for the pleasant introduction as well as for inviting me to share my thoughts on turning “brain drain” into “brain gain.”

For 10 million African-born emigrants, the word “home” is synonymous with the United States, Britain or other country outside of Africa.

Personally, I have lived continuously in the United States for the past 30 years. My last visit to Africa was 17 years ago.

On the day I left Nigeria, I felt sad because I was leaving my family behind. I believed I would return eight years later, probably marry an Igbo girl, and then spend the rest of my life in Nigeria.

But 25 years ago, I fell in love with an American girl, married her three years later, and became eligible to sponsor a Green Card visa for my 35 closest relatives, including my parents and all my siblings, nieces and nephews.

The story of how I brought 35 people to the United States exemplifies how 10 million skilled people have emigrated out of Africa during the past 30 years.

We came to the United States on student visas and then changed our status to become permanent residents and then naturalized citizens. Our new citizenship status helped us sponsor relatives, and also inspired our friends to immigrate here.

Ten million Africans now constitute an invisible nation that resides outside Africa. Although invisible, it is a nation as populous as Angola, Malawi, Zambia or Zimbabwe. If it were to be a nation with distinct borders, it would have an income roughly equivalent to Africa’s gross domestic product.

Although the African Union does not recognize the African Diaspora as a nation, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) acknowledges its economic importance. The IMF estimates the African Diaspora now constitutes the biggest group of foreign investors in Africa.

Take for example Western Union. It estimates that it is not atypical for an immigrant to wire $300 per month to relatives in Africa. If you assume that most Africans living outside Africa send money each month and you do the math, you will agree with the IMF that the African Diaspora is indeed the largest foreign investor in Africa.

What few realize is that Africans who immigrate to the United States contribute 40 times more wealth to the American than to the African economy. According to the United Nations, an African professional working in the United States contributes about $150,000 per year to the U.S. economy.

Again, if you do the math, you will realize that the African professional remitting $300 per month to Africa is contributing 40 times more to the United States economy than to the African one.

On a relative scale, that means for every $300 per month a professional African sends home, that person contributes $12,000 per month to the U.S. economy.

Of course, the issue more important than facts and figures is eliminating poverty in Africa, not merely reducing it by sending money to relatives. Money alone cannot eliminate poverty in Africa, because even one million dollars is a number with no intrinsic value.

Real wealth cannot be measured by money, yet we often confuse money with wealth. Under the status quo, Africa would still remain poor even if we were to send all the money in the world there.

Ask someone who is ill what “wealth” means, and you will get a very different answer than from most other people.

If you were HIV-positive, you would gladly exchange one million dollars to become HIV-negative.

When you give your money to your doctor, that physician helps you convert your money into health – or rather, wealth.

Money cannot teach your children. Teachers can. Money cannot bring electricity to your home. Engineers can. Money cannot cure sick people. Doctors can.

Because it is only a nation’s human capital that can be converted into real wealth, that human capital is much more valuable than its financial capital.

A few years ago, Zambia had 1,600 medical doctors. Today, Zambia has only 400 medical doctors. Kenya retains only 10% of the nurses and doctors trained there. A similar story is told from South Africa to Ghana.

I also speak from my family experiences. After contributing 25 years to Nigerian society as a nurse, my father retired on a $25-per-month pension.

By comparison, my four sisters each earn $25 per hour as nurses in the United States. If my father had had the opportunity my sisters did, he certainly would have immigrated to the United States as a young nurse.

The “brain drain” explains, in part, why affluent Africans fly to London for their medical treatments.

Furthermore, because a significant percentage of African doctors and nurses practice in U.S. hospitals, we can reasonably conclude that African medical schools are de facto serving the American people, not Africa.

A recent World Bank survey shows that African universities are exporting a large percentage of their graduating manpower to the United States. In a given year, the World Bank estimates that 70,000 skilled Africans immigrate to Europe and the United States.

While these 70,000 skilled Africans are fleeing the continent in search of employment and decent wages, 100,000 skilled expatriates who are paid wages higher than the prevailing rate in Europe are hired to replace them.

In Nigeria, the petroleum industry hires about 1,000 skilled expatriates, even though we can find similar skills within the African Diaspora. Instead of developing its own manpower resources, Nigeria prefers to contract out its oil exploration despite the staggeringly high price of having to concede 40% of its profits to foreign oil companies.

In a pre-independence day editorial, the Vanguard (Nigeria) queried: “Why would the optimism of 1960 give way to the despair of 2000?”

My answer is this: Nigeria achieved political independence in 1960, but by the year 2000 had not yet achieved technological independence.

During colonial rule, Nigeria retained only 50% of the profits from oil derived from its own territory. Four decades after this colonial rule ended, the New York Times (December 22, 2002) wrote that “40 percent of the oil revenue goes to Chevron, [and] 60 percent to the [Nigerian] government.”

As a point of comparison, the United States would never permit a Nigerian oil company to retain 40% of the profits from a Texas oilfield.

Our African homelands have paid an extraordinary price for their lack of domestic technological knowledge.

Because of that lack of knowledge, since it gained independence in 1960, Nigeria has relinquished 40% of its oilfields and $200 billion to American and European stockholders.

Because of that lack of knowledge, Nigeria exports crude petroleum, only to import refined petroleum.

Because of that lack of knowledge, Africa exports raw steel, only to import cars that are essentially steel products.

Knowledge is the engine that drives economic growth, and Africa cannot eliminate poverty without first increasing and nurturing its intellectual capital.

Reversing the “brain drain” will increase Africa’s intellectual capital while also increasing its wealth in many, many different ways.

Can the “brain drain” be reversed? My answer is: yes. But in order for it to happen, we must try something different.

At this point, I want to inject a new idea into this dialogue. For my idea to work, it requires that we tap the talents and skills of the African Diaspora. It requires that we create one million high-tech jobs in Africa. It requires that we move one million high-tech jobs from the United States to Africa.

I know you are wondering: How can we move one million jobs from the United States to Africa?

It can be done. In fact, by the year 2015 the U.S. Department of Labor expects to lose an estimated 3.3 million call center jobs to developing nations.

In this area, what we as Africans need to do is develop a strategic plan – one that will persuade multinational companies that it will be more profitable to move their call centers to nations in Africa instead of India.

These high-tech jobs include those in call centers, customer service and help desks – all of which are suitable for unemployed university graduates.

The reason these jobs could now emerge in Africa is that recent technological advances such as the Internet and mobile telephones now make it practical, cheaper and otherwise advantageous to move these services to developing nations, where lower wages prevail.

If Africa succeeds in capturing one million of these high-tech jobs, they could provide more revenues than all the African oilfields. These “greener pastures” would lure back talent and, in turn, create a reverse “brain drain.”

Again, we have a rare and unique window of opportunity to convert projected American job losses into Africa’s job gain, and thus change the “brain drain” to “brain gain.”

However, aggressive action must be taken before this window of opportunity closes. India is a formidable competitor.

Therefore, we need to determine the cost savings realized by outsourcing call center jobs to Africa instead of India. That cost saving will be used as a selling point to corporations interested in outsourcing jobs.

A typical call center employee might be a housewife using a laptop computer and a cell phone to work from her home. As night settles and her children go to bed, she could place a phone call to Los Angeles, which is 10 hours behind her time zone.

An American answers her call and she says, “Good morning, this is Zakiya.” Using a standard, rehearsed script, she tries to sell an American product.

Now that USA-to-Africa telephone calls are as low as 6 cents per minute, it is economically feasible for a telephone sales person to reside in Anglophone Africa while virtually employed in the United States, and – this is important – paying income taxes only to her country in Africa.

I will give one more example of how thousands of call center jobs can be created in Africa.

It is well known that U.S. companies often give up on collecting outstanding account balances of less than $50 each. The reason is that it often costs $60 in American labor to recover that $50.

By comparison, I believe it would cost only $10 in African labor (including the 6 cents per minute phone call) to collect an outstanding balance of $50.

Earlier, the organizers of this Pan African Conference gave me a note containing eleven questions.

The first was: Do skilled Africans have the moral obligation to remain and work in Africa?

I believe those with skills should be encouraged and rewarded to stay, work, and raise their families in Africa. When that happens, a large middle class will be created, thereby reducing the conditions that give rise to civil war and corruption. Then, a true revitalization and renaissance will occur.

The second question was: Should skilled African emigrants be compelled to return to Africa?

I believe controlling emigration will be very difficult. Instead, I recommend the United Nations impose a “brain gain tax” upon those nations benefiting from the “brain drain.”

Each year, the United States creates a brain drain by issuing 135,000 H1-B visas to “outstanding researchers” and persons with “extraordinary ability.”

The U.S. Internal Revenue Service (IRS), working in tangent with the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), could be required to credit one month’s salary, each year, to the country of birth of each immigrant.

Already, the IRS allows U.S. taxpayers to make voluntary contributions to election funds. Similarly, it could allow immigrants to voluntarily pay taxes to their country of birth, instead of to the United States.

The third question was: Why don’t we encourage unemployed Africans to seek employment abroad?

Put differently, if all the nurses and doctors in Africa were to win the U.S. visa lottery, who will operate our hospitals?

If we encourage 8 million talented Africans to emigrate, what will we encourage their remaining 800 million brothers and sisters to do?

The fourth question was: Should we blame the African Diaspora for Africa’s problems?

Yes, the Diaspora should be blamed in part, because the absence it’s created has diminished the continent’s intellectual capital and thus created the vacuum enabling dictators and corruption to flourish.

The likes of Idi Amin, Jean-Bedel Bokassa and Mobutu Sese Seko would not be able to declare themselves president-for-life of nations who have a large, educated middle class.

The fifth question was: Should we not blame Africa’s leaders for siphoning money from Africa’s treasuries?

It becomes a vicious circle: the flight of intellectual capital increases the flight of financial capital which in turn increases again the flight of intellectual capital.

Leadership is a collective process, and “brain drain” reduces the collective brainpower needed to fight corruption and mismanagement.

For example, the leadership of the Central Bank of Nigeria did not call a news conference after Sani Abacha stole $3 billion dollars from it.

The bank’s Governor-General did not go on a hunger strike. He did not report the robbery to the police. He did not file a lawsuit.

Had they the intellectual manpower to counter corruption, the results would have been very different.

The sixth question was: Is it possible to achieve an African renaissance?

Because by definition, a renaissance is the revival and flowering of the arts, literature and sciences, it must be preceded by a growth in the continent’s intellectual capital, or the collective knowledge of the people.

The best African musicians live in France. The top African writers live in the United States or Britain. The soccer superstars live in Europe. It will be impossible to achieve a renaissance without the contributions of the talented.

The seventh question was: For how long has the “brain drain” problem existed?

A common misconception is that the African “brain drain” started 40 years ago.

In reality, it actually began ten times that long. Four hundred years ago, most people of African descent lived in Africa. Today, one in five of African descent live in the Americas. Therefore, measured in numbers, the largest “brain drain” resulted from the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Contrary to what people believed, Africa experienced a brain gain during the first half of the 20th century. Schools, hospitals and banks were built by the British colonialists. These institutions were the visible manifestations of brain gain.

At the end of colonial rule, skilled Europeans fled the continent. Skilled Africans started fleeing the continent in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s. The result was the widespread rise of despotic rulers.

The eighth question was: Is “brain drain” a form of modern slavery?

By the end of the 21st century, people will have different sensibilities and will describe it as modern day slavery.

In the 19th century, which was an Agricultural Age, the U.S. economy needed strong hands to pick cotton, and the young and sturdy were forced into slavery.

In the 21st century, which is an Information Age, the U.S. economy needs persons with “extraordinary ability” and the best and brightest are lured with Green Card visas. Africans who are illiterate or HIV-positive are automatically denied American visas.

The ninth question was: Do you believe that the “brain drain” can be reversed?

As I stated earlier, “brain drain” is a complex and multidimensional problem that can be reversed into “brain gain.”

India is now reversing its “brain drain,” and turning it into “brain gain;” I believe Africa can do the same. But unless we reverse it, the dream of an African renaissance will remain an elusive one.

The tenth question was: Can we blame globalization as a cause of brain drain?

Globalization began 400 years ago with the trans-Atlantic slave trade that brought the ancestors of 200 million Africans now living in the Americas. It has accelerated because the Internet and cell phone now enable you to communicate instantaneously with any person on the globe.

Overall, globalization is a force that is denationalizing the wealth of developing nations. Economists have confirmed that the rich nations are getting richer while the poor ones are getting poorer.

We also know that the globalization process is increasing the foreign debts of developing nations, accelerating the flight of financial and intellectual capital to western nations.

The economics of offshoring will force multinational corporations to outsource to developing nations where lower wages prevail.

To remain competitive and profitable, companies will be forced to reduce costs by hiring five-dollars-an-hour computer programmers living in Third World countries and lay off expensive American programmers that demand $50 an hour.

In the long term, offshoring will reverse the flight of financial and intellectual capital from western nations to the Third World.

The eleventh question was: Why have I lived in the United States for 30 continuous years?

Africa has bitten at my soul since I left. My roots are still in Africa. My house is filled with Africana – food, paintings, music, and clothes – to remind me of Africa.

I long to visit the motherland, but I must confess that when Africa called me to return home, I couldn’t answer that call.

The reason is that I work on creating new knowledge that could be used to redesign supercomputers. The most powerful supercomputers cost $120 million each and Nigeria could not afford to buy one for me. I created the knowledge that the power of thousands of processors can be harnessed; this knowledge, in turn, inspired the reinvention of vector supercomputers into massively parallel supercomputers.

New knowledge must precede new technological products and the supercomputer of today will become the personal computer of tomorrow.

And so to answer your question: even though I reside in the U.S. the knowledge that I created is now materializing into better personal computers purchased by Africans.

Finally, millions of high-tech jobs can be performed from Africa, but may instead be lost to India. We must identify the millions of jobs that will be more profitable when transferred from the United States to Africa.

Doing so will enable us to create a brain drain from the United States and convert it to a brain gain for Africa.

Thank you again.

Culled from: www.emeagwali.com

InlandTown! 2015.